Alex Salmond: A great man with a great flaw

Some hard truths about the former leader of the SNP, who has died aged 69

Travelling around Scotland by train in the past couple of weeks I have seen the same sight in numerous villages and towns: Saltire flags flying at half mast.

To committed Scottish nationalists the loss of Alex Salmond is felt deeply. This was a man who, in their world view, came close to fulfilling Scotland’s destiny as an independent nation.

More than once in recent days I have heard the former first minister identified as a Scottish hero on a par with Robert the Bruce and William Wallace. To non-believers this feels faintly ridiculous. To the faithful it is a self-evident truth.

What struck me about the reaction of some independence supporters was their anger. I know anger is one of the Kübler-Ross five stages of grief, coming between denial and bargaining, but some reactions I saw came close to rage.

One acquaintance of mine was incandescent at a routine statement put out by the UK foreign office, saying they were helping “the family of a British national” who had died in North Macedonia. A British national! The gall! How dare they!

The immediate aftermath of Salmond’s death felt somewhat surreal. There was no protocol for the death abroad of a former first minister. Would the body be repatriated in the usual manner for a normal citizen? Would the RAF fly the coffin home, as suggested by one of Salmond’s old pals in the Commons? The UK and Scottish governments could not seem to agree on a course of action.

In the end Sir Tom Hunter, the billionaire philanthropist, stepped in with the offer of a private flight. You could detect a general sigh of relief at this news. Even someone like me, not a great fan of Salmond, could see that bringing his body home in a crate on a commercial flight would be undignified, given his status as a former FM.

The hesitation over what to do was a symptom of a broader sense of unease. Salmond was one of the towering political figures of our age, but his glory days were very much behind him. In recent opinion polls he was one of the least popular politicians in Scotland. His fall from grace after the 2014 independence referendum was precipitous and comprehensive. His new political party, a vanity project called Alba, won just 11,784 votes across the whole of Scotland in the UK general election in July. The party fielded 19 candidates, giving each an average of 620 votes.

There was a deeper problem too: the damage done to Salmond’s legacy by multiple accusations of sexual misconduct, first in a Scottish government disciplinary process and then in a sensational criminal trial at the High Court on Edinburgh’s Royal Mile, in which he was ultimately cleared of any criminality.

As a consequence, the customary paeans of praise that follow the death of any public figure were necessarily hedged, qualified and conditional.

When news of Salmond’s death broke at teatime on Saturday October 12 I was called by The Sunday Times and asked to write a piece on “the Alex Salmond I knew”.

A thousand words written in two hours is never going to be fully considered and the first two sentences conveyed the difficulty faced by all obituarists in the coming days.

To some Alex Salmond was a hero, a political genius whose intellect, tenacity and personality almost broke up Britain. For others he was a predator who abused the power of high office to prey on women.

What I was trying to convey was that both were true, and neither reckoning was sufficient without the other.

In the following days I was astonished at the number of people who could see only the hero, and were wilfully blind to the predator.

At Salmond’s funeral on Tuesday in the Aberdeenshire village of Strichen, a member of a nationalist dynasty gave one of the eulogies. Fergus Ewing MSP, son of the former SNP president Winnie Ewing, ended his speech with a promise:

Ladies and gentlemen, given the remarkable achievements of his life, I cannot in this short eulogy do justice to Alex. But something that I can do, working with many others – something that I have sought to do when Alex was with us – is to seek justice for Alex. And for the cause of truth and democracy. In that task I am devoted. That is for one day…but not for this day.

Ewing was less coy in an article a few days earlier for my own newspaper, The Times:

In the past three years, it was my privilege to work with Alex on all sorts of matters. By far the most important of all was to obtain truth and justice for the way he was the subject of what I believe was a concerted campaign by some of the ‘top’ people in the land. It was a malevolent and wicked campaign to discredit him, get him charged, prosecuted then convicted and jailed. Had they succeeded, he would, I fear, have died in a prison cell.

It is not at all a matter of clearing his name. His name was cleared when he trounced the Scottish government in his judicial review and then when he was acquitted of the charges that were brought against him. It is about justice. This is an endeavour of such importance that, until the truth of this scandal is exposed, Scotland as a country is diminished.

Alex, you were my dear dear friend and I weep for you and for Moira and your family, who were devoted to you. But after the tears of grief have dried, I will continue to devote myself to securing that truth and justice that you fought for and deserve. We worked on that together. You are gone, but will always be with me. Wherever you are now, you know that is precisely what I and many others shall do.

This was a call for vengeance, plain and simple. Its language was actually quite mild compared to some other commentaries from loyal Salmondistas. As for comments on social media, well, you can imagine.

Who is the target for this vengeance? The list is long. It includes Nicola Sturgeon, Salmond’s successor as first minister. It includes senior civil servants who were involved in the disciplinary action against Salmond. It includes senior SNP staffers. It includes career lawyers in the Crown Office. It includes senior detectives at Police Scotland. It includes a number of prominent journalists. And, most of all, it includes more than a dozen women who gave police their accounts of sexual assault and indecent assault at Salmond’s hands.

I now realise with a heavy heart that Salmond’s death does not bring this sorry story to an end. Any hope of that was short-lived. In fact we can expect a redoubling of efforts by Salmond’s acolytes to avenge him and humble his accusers. I know some of the women involved and I know they regard this prospect with horror.

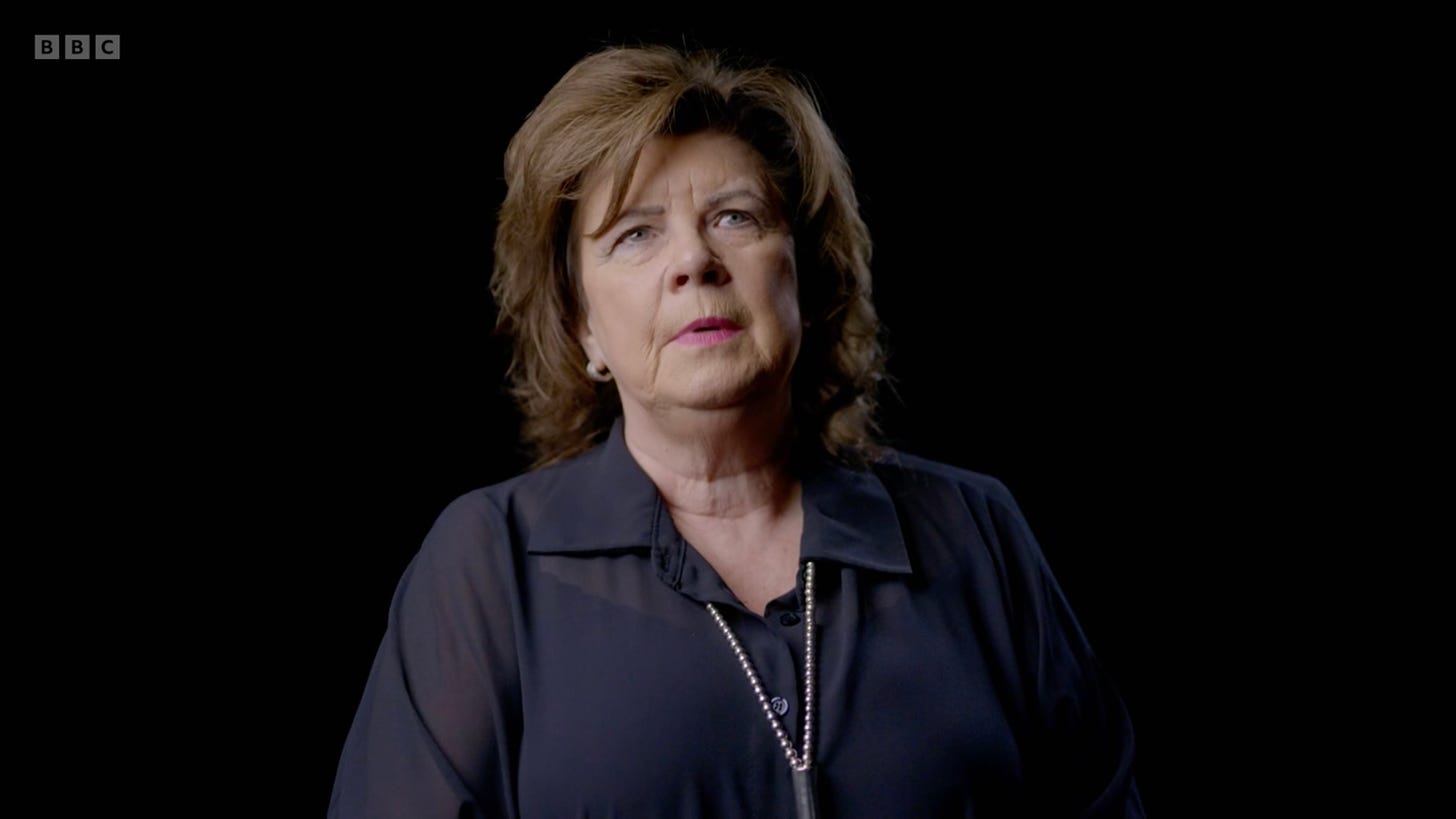

On Wednesday night BBC1 broadcast an hour-long TV documentary about the life and times of Alex Salmond. I was one of the interviewees. You can watch it here.

Perhaps inevitably, the two most potent contributions were from women.

The actor Elaine C Smith, a heroine of the independence movement, said the key factor in Salmond’s behaviour towards his female staff was clear. She said: “This is all about power.” From a political and feminist point of view, she said, his admitted behaviour was “unforgivable”.

Libby Brooks, a journalist with The Guardian, spoke of the difficulty faced by the media in finding the right tone to talk about Salmond, given the shocking circumstances of his sudden death.

“All of that has to be treated with dignity and respect,” she said. “My question is whether the same dignity and respect is being afforded to the women who made complaints about his behaviour.”

In my Times column last week I tried my best to reorientate the conversation in the wake of Salmond’s death.

Across the world the #MeToo phenomenon was a reckoning for many powerful men who had abused positions of trust. The women in the Salmond case were among many thousands in similar circumstances who stepped forward.

The courage of these women, a number of whom I know personally, was exemplary. Ultimately they did not receive the outcome they hoped for. Salmond was acquitted on all counts after a fair trial in the High Court. They always knew that was a possibility.

For these women now to be pursued for their bravery, to be punished for speaking up, to be condemned as liars, is outrageous. Yet it seems there are plenty of folk who are entirely happy to believe one man instead of a dozen women. Not all of Salmond’s disciples go this far. But many do.

There is something medieval about the way these women are now being vilified, even to the extent of being threatened with the publication of their identities, in breach of the law that rightly protects the privacy of complainants in such cases. For too many of Salmond’s supporters these women are mere collateral damage in the noble cause of avenging their hero.

I feel a need to take aside those howling for retribution and have a quiet, felicitous word with them. Especially the men. I want to ask them if they are OK. What deep hurt is the source of their rage? Where does their vile misogyny come from? What damage was done to them in the past by a woman? And isn’t it time they dealt with it like a grown-up? Isn’t it time they dealt with it like a man?

I understand why feelings are raw within the nationalist movement. The fight for independence has stalled. The promise of Yes Scotland has come to nothing. There is no realistic prospect of a second referendum. At the general election the SNP sustained a bloody nose. For Alba, the party founded by Salmond as a vehicle for a return to Holyrood, a breakthrough remains elusive. The unexpected death of the movement’s most charismatic figure feels like the end of all hope.

The least useful response to these cumulative hurts is to wallow in a shallow puddle of muddy self-deceit. Salmond was not destroyed by a conspiracy. He was destroyed by his own misdeeds catching up with him. He was a great man with a great weakness. That weakness was for young female subordinates, a story as old as the hills.

Perhaps it is necessary to revisit the conspiracy theory and hold it up to the light. In the 2021 Holyrood committee of inquiry into the Scottish government’s handling of the saga, there was one morning when Salmond declared he was going to prove there was a plot to destroy him.

I wrote about this at the time in my column:

Salmond said that every word of his testimony could be backed up by documentary evidence. So when he was challenged to justify his assertion that he was the victim of a “malicious and concerted” plot, he had an answer ready. Six pieces of evidence, he said, provided the “inescapable conclusion” that he was framed.

At this point I sat forward in my chair and turned to a fresh page in my reporter’s notebook. In such a long and tortuous inquiry a concise six-point summary could be the moment when Salmond’s argument came into sharp focus and demonstrated its clarity and power.

Alas, it failed to deliver on that promise. The six points were as follows:

1. Salmond’s key accusation was that civil service harassment policy was extended to apply to former ministers just to ensnare him. A retrospective approach was, he said, inherently unfair, and had been conjured up only to nail him.

This fails the credibility test when you recall the context of the #MeToo movement at that time. An important element of the debate was that women should feel empowered to talk about their experiences at the hands of their bosses, even if the incidents had occurred some years in the past.

In fact, since then, retrospectivity in harassment cases has been built into legislation covering the behaviour of MSPs, and similar measures are coming into force at Westminster and the Welsh Senedd. Retrospectivity is not a weird idea cooked up for the purpose of pursuing Alex Salmond. On the contrary, it is a rational, commonsense reform that has become the norm.

2. Salmond painted a dark, sinister picture of a meeting between Sturgeon and Leslie Evans, permanent secretary of the Scottish government, in which emerging policy on harassment was tweaked so that Evans became the key decision maker. Previously the first minister also had a role. Salmond said that this was suspect because Evans had been at this point aware of the accusations against him.

I confess I find Salmond’s reasoning here opaque. His argument that Sturgeon conspired against him is not exactly helped by the fact that her role in the disciplinary process was scaled back. Perhaps it seems sinister only if you approach the facts with maximum prejudice or deep paranoia. Or both.

3. Salmond said it was “highly significant” that the crown agent tried to give police a copy of the Scottish government investigation into his alleged harassment of female employees. The police declined to take it, saying they did not want it to colour their own inquiries. Again, the sinister aspect of this seems only to be in the mind of the former first minister. Indeed it would have been more sinister if the opposite had happened, and an attempt had been made to prevent the police from gaining access to the investigation’s findings.

4. Salmond pointed an accusatory finger at the Scottish government’s refusal to publish legal advice it received from eminent QCs. This related to the civil case he brought and won against the government over the fairness of its disciplinary process. Salmond believes that the government cynically delayed the civil case, against legal advice, in the hope it would be overtaken by the criminal trial.

The problem here for Salmond is that this is a perfectly rational explanation. Delay made sense. Why unnecessarily defend yourself against someone who could be in jail in a few months? If Salmond had been convicted of sex crimes, the fairness or otherwise of a civil service disciplinary process would have been a moot point.

5. Salmond argued that it was unacceptable for SNP officials to start digging for evidence of his alleged misbehaviour once the police were involved. Really? Imagine if the former boss of a widget company was accused of stealing cash from employees’ wallets and purses. Would a manager be justified in checking to see if staff and former colleagues had relevant information the police might find useful, leaving no stone unturned?

6. Salmond said that private messages to SNP staff from Peter Murrell, the party chief executive and Sturgeon’s husband, were “probably the most shocking thing that I had ever seen in my life”. Murrell had urged staff to put pressure on the police to widen the investigation.

What I detect here is a failure by Salmond, once the most powerful man in the land, to adjust to being a private citizen. For decades he had dozens of people amplifying his voice, clearing up his mistakes, deflecting attacks on his actions and his motives. That these same people might no longer want to do so is, to his mind, an outrage.

Alex Salmond’s six points were meant to summarise Nicola Sturgeon’s guilt. All they did was demonstrate the arid emptiness of his accusations.

The evidence was not even circumstantial. It was delusional.

As 2021 came to a close I wrote a Times column that tried to make sense of a year in which the very fabric of of Scottish democracy had at times felt fragile:

This was the year Scotland survived an attempted coup. It was the year the nation witnessed a bid to overthrow its elected leader with conspiracy theories and falsehoods. It was the year of an insurgent effort to undermine public confidence in the machinery of the state: its parliament, its police, its prosecutors, its judiciary. It was the year Alex Salmond tried to bring down Nicola Sturgeon.

I call it an attempted coup because it matches the criteria of renegade bids for power in parts of the world that seldom appear on a bucket list. In particular, I am talking about Salmond’s efforts to convince Scots their civic institutions were riddled with corruption, that the separation of powers between executive, legislature and judiciary were fatally undermined. Salmond tried to persuade us Scotland was broken.

Given such chaos only the return of the nation’s strongest, best-loved and most sorely wronged former leader could restore Caledonia, stern and wild, to her rightful glory. At least that is what seems to have been going through Salmond’s mind as he marshalled his arguments for the Holyrood inquiry into the handling of accusations of his alleged sexual misconduct against female staff when first minster. The hearing, with MSPs questioning Salmond and Sturgeon in February and March, was political theatre at its most compelling. It became, in effect, a trial of Sturgeon’s fitness for office but there was something else in the dock too. She had to defend not only her own actions but the legitimacy of the Scottish body politic as a whole.

Circumstances favoured Salmond. Half of Scotland opposed Sturgeon’s aim of independence and might therefore be disinclined to give her the benefit of the doubt. The other half was itself divided, with many nationalists unhappy about her lack of progress on a Scottish breakaway. Within the independence movement there were questions about her sincerity and commitment. In the SNP ranks there was disquiet about the grip on power of one household: Sturgeon and her husband, Peter Murrell, the party’s chief executive for the past 22 years.

Salmond knew which buttons to press. He knew people tend to think the worst of politicians. He knew how fear, scepticism and ignorance could be weaponised. Most insidious of all, he knew how legitimate concerns about the architecture of Scottish devolution, including the institutional weakness of the Holyrood parliament, could be played. His aim was to destroy Sturgeon and reduce Scotland’s party of government to a smoking ruin.

Ultimately he failed. Salmond’s coup was undone by the personal weaknesses all too apparent to those who had followed his career over the past three decades. Uppermost among these were arrogance and hubris. The grand conspiracy he confected was credible to Salmond because he required a foe that matched his inflated sense of himself. For him to be brought low must require, by his own reckoning, the mass mobilisation of all arms of the devolution state, with Lilliputian civil servants and detectives and advocates and parliamentarians scurrying around in a futile attempt to peg his mightiness to the ground.

While this made sense to him, the rest of the world recognised it as a Grand Guignol fantasy, outlandish and laughably implausible. Salmond’s formidable political savvy did not extend to a clear-sighted view of what the world thought of him. In truth what people saw was not a wronged hero but a soiled has-been. A court had cleared Salmond of criminality over multiple charges of sexual assault including attempted rape. Yet the picture painted, in part by his own defence, was of a dirty old man who abused his position of power to be serially inappropriate.

The attempted coup was rebuffed. That is testament to the good sense and judgment of the Scottish public as much as anything else. People trusted their instincts and decided Salmond’s wild accusations were not credible. In May a poll showed only 9 per cent of Scots had a favourable opinion of him, while 74 per cent held an unfavourable view. In the Holyrood election Salmond’s new Alba party won 1.66 per cent of the vote, humiliation for a man to whom humility was a stranger.

Who knows, perhaps Fergus Ewing has recordings of secret telephone conversations between the permanent secretary, the chief constable, the first minister, the lord advocate, the crown agent, the chief executive of the SNP and the editor of the Daily Record. Perhaps he can demonstrate a conspiracy, rather than just a conspiracy theory.

I doubt it.

In my interview for this week’s BBC documentary I made a point of paying tribute to Salmond’s political savvy, his communication skills, his tenacity in persuading the SNP to embrace devolution as a stepping stone to independence.

Wrapping up, the BBC reporter sprung a question on me. If I had to describe Alex Salmond in just three words, what would they be?

I hummed and hawed for a few seconds before saying: “A flawed man.”

-o0o-

The Jaggy Thistle is a reader-supported publication. For further details of the benefits of a paid subscription, press this button:

Leave a comment by pressing this button:

Know somebody who might like this post? Please feel free to share it with them, or more widely on your social media. Use this button:

“A chield’s amang you takin notes, And faith he’ll prent it.”

Robert Burns

-o0o-

Forensically fair.

I think that’s a very fair assessment of the man. “He knew which buttons to press”. I think that sentence for me summed up his whole modus operandi in gaining support for independence. He knew the arguments to make, however over simplistic or inaccurate, that would resonate with the great many left so helpless and left behind by the Thatcher years and several more years of Tory government immediately leading up to the referendum. “He knew which buttons to press” would be a good epitaph for him, I think.