My dad the typewriter salesman

How a chance discovery told me something I didn't know about my father

I was a weird kid. When other children my age were joining the Tufty Club I was signing up as a member of the Goon Show Preservation Society. I awaited the monthly newsletters with an excitement most youngsters reserved for Christmas.

My other main hobby was examining my father’s copy of Exchange & Mart for small ads selling guns and knives. Yes, guns and knives. Crossbows too. And swords, especially samurai swords.

Like I say, weird kid.

I did have one thing in common with other children. I liked collecting. But not normal collecting. While my pals were swapping football cards or the silver coins you got from petrol stations during World Cup tournaments, I was collecting, well, business cards.

Even today I can see how weird this looks. Panini cards are cool. Business cards are not cool.

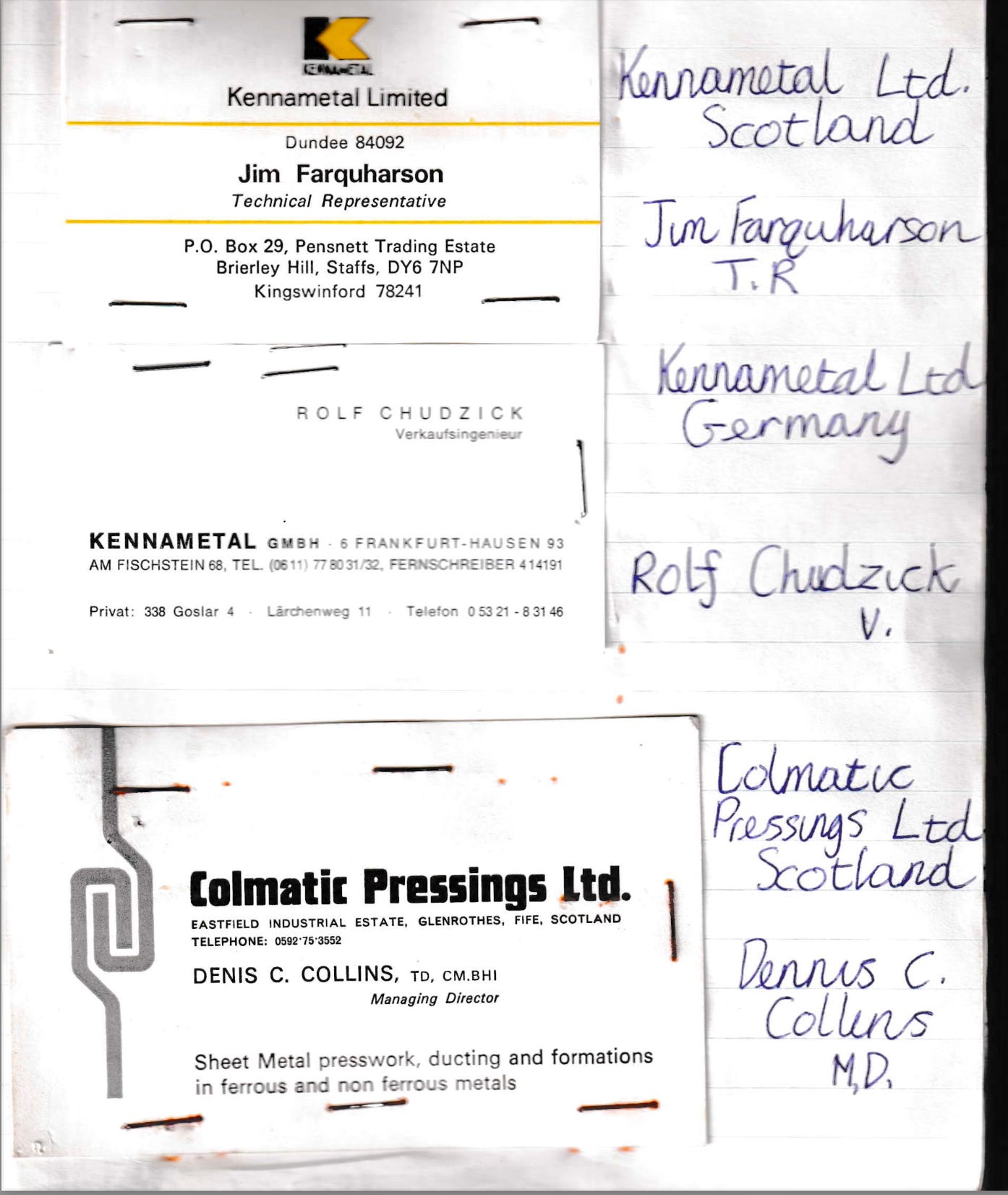

I had forgotten all about this. I was only reminded recently while clearing out my elderly mother’s home after she went into care. There was a large box of family ephemera. In it I found this:

By the way, did you read the Substack post about the bookseller who got into trouble when an overweight woman came into the shop and asked where to find the exercise books? The bookseller pointed to the “health and fitness” section. The woman was outraged. She meant exercise books she could write in.

I digress. I picked up this red jotter with a jolt of recollection. This memory had lain dormant and undisturbed for 50 years. Perhaps I preferred to remember cool stuff about my childhood. Like the time I won a go-cart race in a “piler” made by my dad from an old pram chassis. Or when I watched Scotland beat England at Hampden, perfectly positioned to see Kenny Dalglish nutmeg the England goalie Ray Clemence. And yet here was the weird evidence I could not deny.

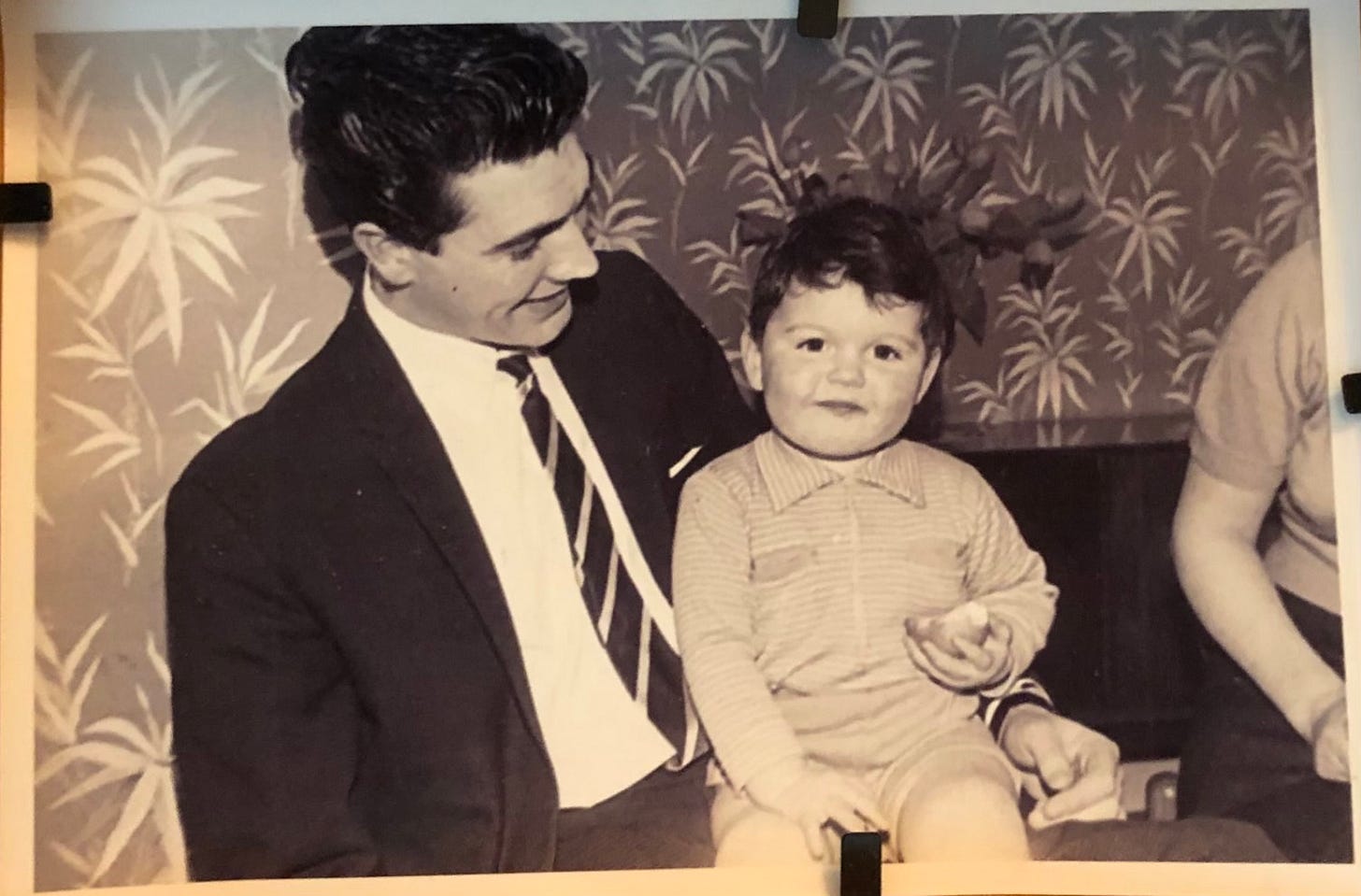

My only excuse is that to me, aged eight or nine, business cards were exotic. They were a novelty. My father, Jim, had spent most of his working life in a factory. He was a blue-collar worker, a toolmaker to be precise. Toolmakers did not have business cards. Nobody in our extended family had business cards.

As I write, here in early 2024, the job of toolmaker is part of public discourse. The reason is Sir Keir Starmer. His dad was a toolmaker, a fact the Labour leader is fond of mentioning to boost his working class credibility.

When Starmer became Labour leader I liked to tell people he and I had three things in common: we were the same age; our dads were both toolmakers; and we both had great hair.

I digress, again.

From the toolmaker discourse around Starmer it is clear most people have no idea what a toolmaker does. Most people think a toolmaker makes hammers and chisels. They think a toolmaker makes the kind of tools you find in a toolbox. They have no inkling that toolmakers are the princes (and princesses these days) of the factory floor. They are skilled tradespeople playing a crucial role in manufacturing industry.

Simply put, a toolmaker makes the tools a factory uses to make stuff. My dad used to work for Timex in Dundee, making watches. With tolerances of a thousandth of an inch he would, for example, a use a lathe to shape a die that was then used to stamp out the tiny component parts of a watch mechanism from thin sheets of metal.

This was skilled work. And dangerous. One of his fingers had a chunk missing from a mishap with a lathe. It could have been a lot worse.

Engineering was a fickle industry in Dundee in the 1960s and 1970s, vulnerable to changing technologies and a shift in manufacturing to the Far East and the Indian subcontinent.

So there were times when my father was unemployed. Orders dried up. Two of the three Timex factories in Dundee closed. There were a lot of skilled men looking for work. My dad, with a wife and two young sons to support, took whatever jobs he could find.

To his children’s delight he spent a summer driving an ice cream van. For us, this was the stuff of dreams. His patch was the Ardler housing estate in the north of of Dundee. Ardler had six 17-storey tower blocks with 1,788 flats in all. That is a lot of kids who like ice cream.

It could be stressful. Arguments were not uncommon. Children who had been entrusted with a pound note and sent for ice cream sometimes returned home with incorrect change. Angry dads would then remonstrate at the van. The possibility that the child may have pocketed the cash themselves rarely seemed to occur to the parent.

For a while Jim was an encyclopaedia salesman. He went door-to-door in the leafier parts of Dundee and sold the idea of knowledge. At home, we had a grand total of five books. The imparting of knowledge was almost entirely oral.

I find it hard to imagine him as a cold caller on a stranger’s doorstep. My father was not a gregarious man. I would not have put him down as a natural door-to-door salesman.

And yet, on reflection, maybe I am doing him a disservice. My father was quiet-spoken and easeful. There was a calm about him. People relaxed in his company and felt able to be themselves.

All this was apparent the moment you met him. I saw this happen many times when I was growing up and it was a good thing for a son to see. His warmth invited you in. He was a place of safety. There was confidence there, true, but not a trace of arrogance.

So, yes, maybe my dad was a good salesman after all. My business card collection seems to suggest so, anyway.

The card collection is mostly people in the machine tool industry. My dad ended up a salesman for the firms that made the tools he once used on the factory floor, companies such as Kennametal and Unbrako. His hands-on experience meant he could speak with authority about how they worked. He could also give a practical demonstration when required.

The cards gathered from his customers and colleagues speak of a heavy manufacturing age now largely gone. Steel fabricators in Auchtermuchty. Iron works in Livingston. Cutting tools in Arbroath. Sheet metal pressing in Glenrothes. Manufacturers of screwed fasteners in Wolverhampton. Brassfounders in Silvermills, in Edinburgh, near where I now live.

But what was this?

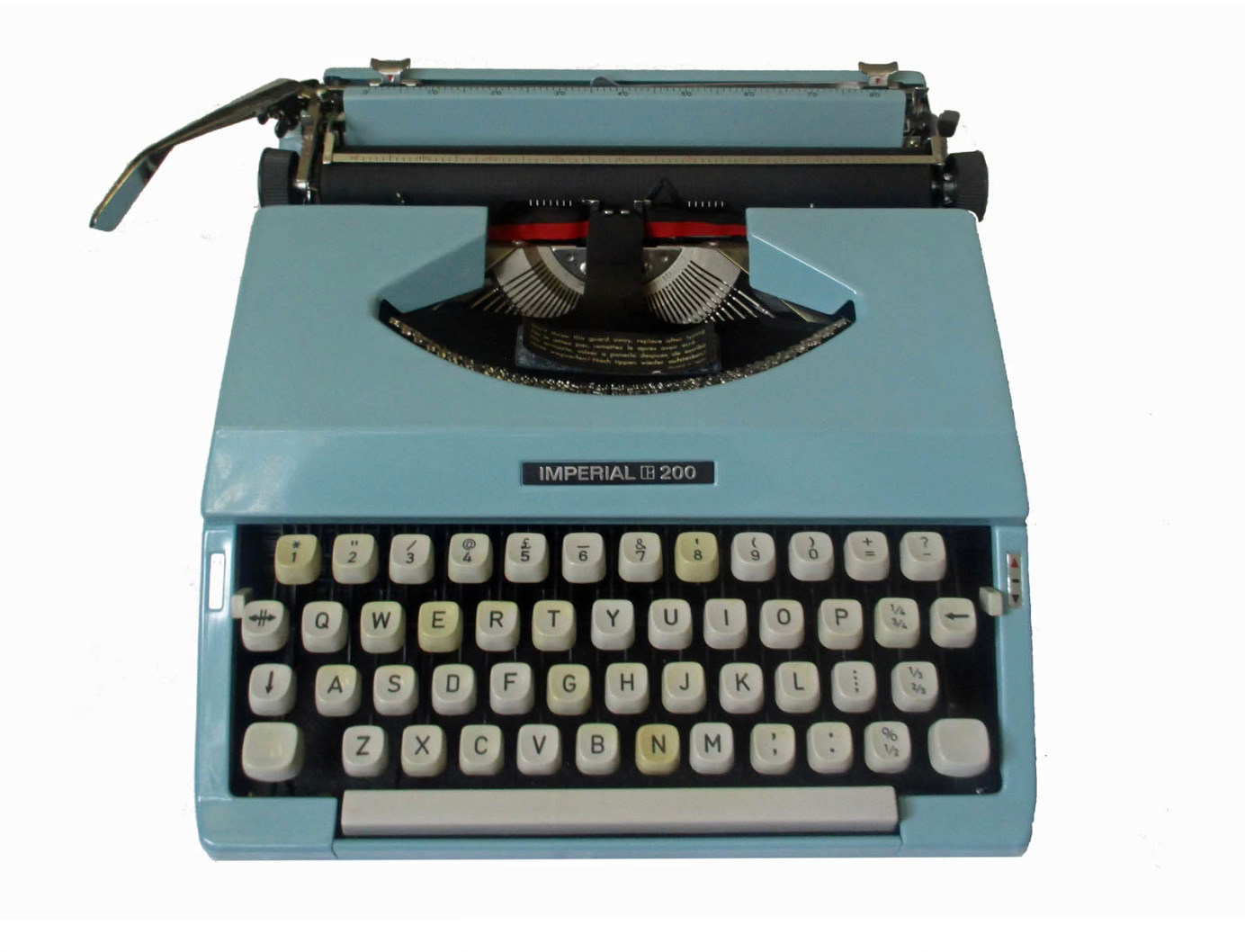

The card at the bottom of the page made me do a double take. James Farquharson, representative for Imperial Typewriters? My dad was a typewriter salesman?

I had no recollection of this. Then again, much of my childhood is a blur. Some details are pin sharp. Smells. Textures. Sensations. But much of it is a disorienting swirl of unreliable memory fragmented by grief.

My father died in a car crash on December 10, 1976. He was 38 years old. At the time my brother was 13 and I was 14. Our mother Nancy, also 38, was pregnant at the time her husband died.

I wrote about this experience here, as a story about fathers and sons and love and loss. I wrote it as a reckoning with myself, an attempt to confront a defining moment in my life. A kindly sub-editor gave the piece a simple two-word headline: “Letting go”. I honestly had never thought about it in those terms, but he was right. The piece was about letting go.

And it helped. It really did. It allowed me to move on with my life. I had written about my dad as honestly as I could. I had declared my love for him. I hoped I had done him justice.

It helped, too, that I felt I knew all there was to to know about my dad. All that was knowable at this distance, at any rate. These days my lovely mum is in her mid-80s and has dementia. She lives in a perpetual present. Everything she once knew about my father has been forgotten. If I wanted to ask her anything about him, I have left it too late.

But here was new information. Here was something that reopened a box in my head that had been closed for many years. Not only closed but stored away at the back of a cupboard in my mind, sorted, while I got on with the rest of my life.

And not just any new information. This was big news. My dad had been a typewriter salesman. This was thrilling. It is hard for me to overstate this, but I absolutely adore typewriters. I love the mechanics of them. I love their design. I love how they sound. I love what they do. One of my favourite Substacks is by Kent Peterson, simply because he types up his thoughts on a typewriter and then posts an image of the result. I have the word processing app for my iPad developed by typewriter enthusiast Tom Hanks that replicates the sounds and typefaces of classic typewriters down the ages. One of my favourite songs has the line: “And in your hands I sleep just like a drummer / And wake up with the thunder of your typewriter every night.” I totally loved the documentary California Typewriter and made my family sit down and watch it.

I now have a question in my mind. Does my love of typewriters simply come from the fact I am a journalist of a certain age who began his career before the age of computers? Or is something else going on here, something previously hidden from me, something only now revealing itself that might explain my life? Does my love of typewriters come from my dad being a typewriter salesman when I was a child? Did that, in some way, somehow, make me a writer?

I have zero memories to go on. I have no recollection of this job my father did, and neither does my brother. It is not part of family lore like many of his other jobs. I do not recall there ever being a typewriter in the house. Nor do I remember ever going to the Leishman & Hughes office at 17 Albert Square, Dundee, which is now an anonymous office building. Although thanks to the PictureThisScotland account on Twitter I have this photo of the company’s office in George Street, Edinburgh, in the 1960s:

A common question I have been asked down the years is: “What made you decide to be a journalist?” A simple inquiry but one that always leaves me slightly flummoxed. I have improvised an answer of sorts. I tell how, when asked at primary school on a Monday morning to write down what I had done at the weekend, I would cover pages and pages with my awful handwriting while others could only manage a few lines. I say I was good at English. I say the trauma of my teenage years seems to have fine-tuned my emotional intelligence to make me a good observer of people.

The truth is I really do not know. For most of my childhood I had a very firm, weirdly specific ambition to be a Royal Air Force police dog handler. The interest in journalism, to spend my days hammering at a typewriter, only came in my mid-teens after my father died. He never knew I wanted to be a reporter.

I have a pretty good imagination. I could, if I tried hard enough, imagine a narrative of my dad bringing home one of the Imperial typewriters he was selling, letting me and brother play on it, explaining to us how it worked, switching the ribbon from black to red, watching us coo over this fabulous machine. I could write that romantic script.

It would be fiction, not memoir. But what if it was true?

I have cried more in the past few months than I have in the past few years. I have good reason. My mother’s mental decline and the necessity of her going into care has been tough on my brother and me. My emotions have felt close to the surface for a while. And despite the difficulties with my mum, I know this is partly down to my dad. It is connected to reopening that box I had put away in my mind for good.

Call it a lesson learned. It was never sorted. It was never over. These things never are.

I am glad the box has been reopened. Even though I now have more questions than answers.

I am glad I still have something to learn about my father.

-o0o-

What did you think of this post? Have you made similar discoveries when going through old family papers? Have your say in the comments.

Know somebody who might like this post? Please feel free to share it.

Are you a subscriber to The Jaggy Thistle? If so, thank you! Your support is much appreciated. You aren’t a subscriber? Subscribe now!

Thank you Gregor. That is a lot of similarities! Make sure to say hello if our paths cross in the Ferry.

What a brilliant article. Thanks for sharing. And I think the business card collection is superb. I can remember being given my first as a trainee solicitor in 1995 (when folk still exchanged business cards; something that has stopped happening in the legal profession at least). We were all desperate to give a card or two away, and I posted one each to my Mum and Dad in Dundee. I think all of us gave them to family.