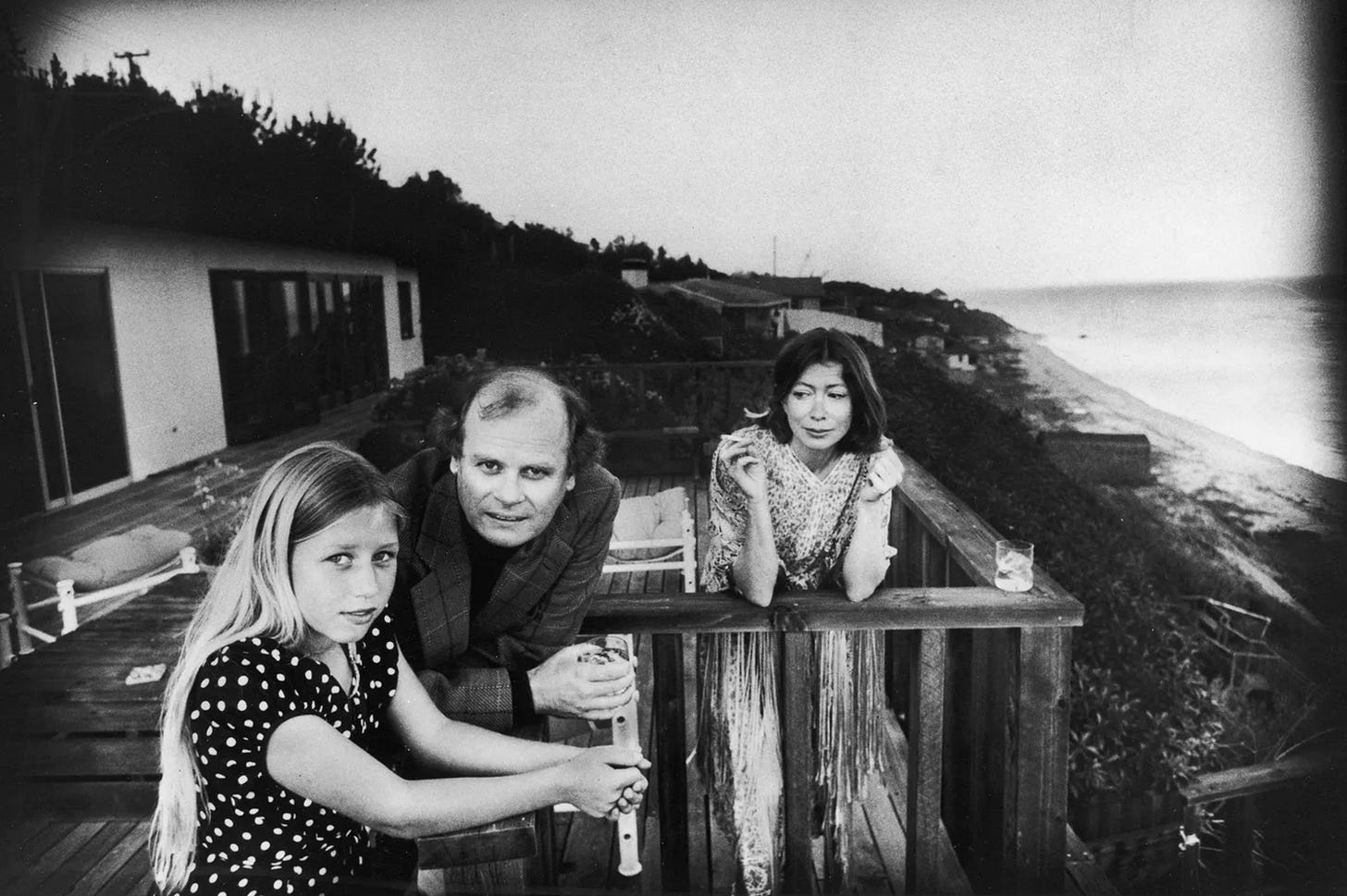

In a new essay in the London Review of Books, Andrew O’Hagan parses this famous picture of Joan Didion with her husband John Gregory Dunne and their daughter Quintana on the deck of their home in California in 1976.

As a result of Didion’s essays and of photographs we’ve seen, those of us who didn’t know Quintana are likely to picture her in Malibu, somewhere her mother called a place of ‘isolation and adversity’. ‘We moved to this house on the highway in the year of our daughter’s fifth birthday,’ she writes in ‘Quiet Days in Malibu’, and ‘in the year of her twelfth it rained until the highway collapsed, and one of her friends drowned at Zuma Beach, a casualty of Quaaludes.’ John Bryson’s photograph of the family on that warm promontory from 1976 now offers a premonition of the cold front ahead of them. Quintana looks at the camera as if suspicious at being seen, while Didion, next to her husband, John Gregory Dunne, is balanced between a whisky glass and a lit cigarette, looking at Quintana. The difficulties are already inscribed in the dry air between them.

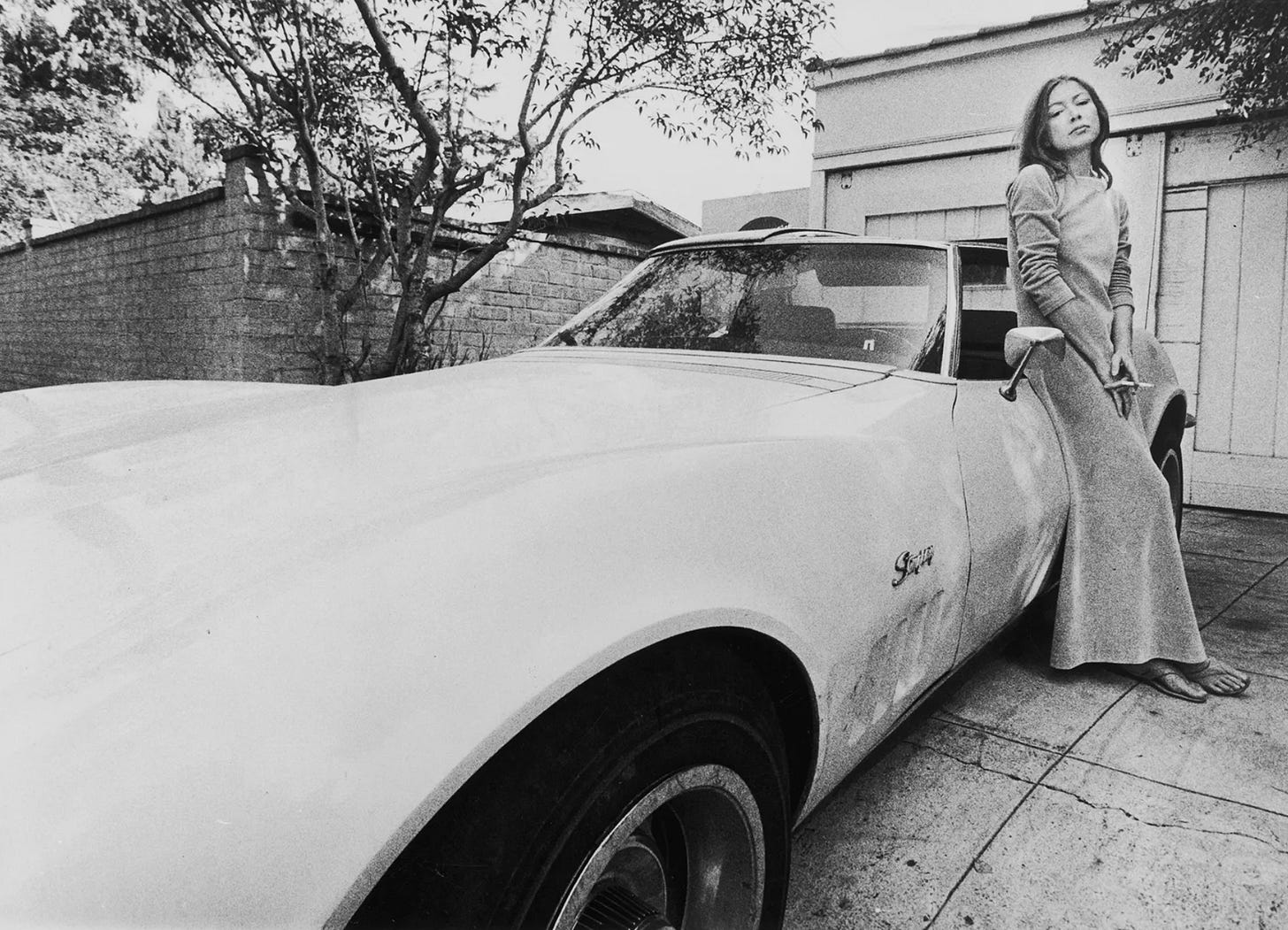

I must have seen this photograph a hundred times. Every devoted fan of Didion - there are many of us in journalism - is familiar with it. Previously I regarded this image as evidence of the gilded life the Didion-Dunnes, with a Corvette in the drive, ice tinkling in a crystal tumbler and deadlines so distant they could barely be seen by the naked eye.

Now I will never again be able to see this photograph without a sense of unease. This is tremendous writing, especially Didion “balanced between a whisky glass and a lit cigarette”. A sense of precarity hangs over the whole of O’Hagan’s piece as it charts Didion’s troubled relationship with her doomed daughter.

The simple reason for me writing this Jaggy Thistle post today is to urge you to read O’Hagan’s 6,300-word essay, which takes the form of a review of three recent Didion-related books, including Notes to John, an edited collection of the private memos she wrote to her husband about her sessions with a psychoanalyst.

The publication of Notes to John has prompted a lively debate about whether it is morally justifiable for Didion’s literary executors to authorise the publication of material that meets all definitions of the word raw.

O’Hagan, I think, provides the final word on this stushie:

She would have been mortified at these notes being turned into a ‘book’, and that’s because they are not a book, not even provisionally. They are intimate notes she wrote to keep her husband abreast of a developing medical situation. Even your average quality-control freak (and Didion was above average here) wouldn’t want the shrapnel of their scattergun anxieties and thoughts to be displayed like this. The idea that authors should go around destroying notes and manuscripts they don’t intend for publication is only ever posited by people who aren’t writers. If Didion had wanted these notes out in the world, she would have arranged it. Every serious writer has notes and drafts that are not published, and never will be, for the simple reason that they are not publishable. We keep everything, not in the expectation that it will one day end up in Barnes & Noble, but because we know from experience that it might prove useful to jog a memory, fashion a scene or recall a character. I don’t know a single writer who spends time rummaging through their boxes looking for things to burn.

As I have written on The Jaggy Thistle before, I am a big fan of O’Hagan’s journalism. Even, if pushed, preferring it to his fiction. In support of this judgement I offer the first two paragraphs of his LRB essay:

On 6 December 2000, during a snowstorm, Joan Didion was sitting in the waiting room of an office in Manhattan reading a copy of National Geographic. She was lost in an article about polar bears and their cubs and regretted having to stop reading when her therapist called her into his room. Roger MacKinnon, who was then 73, was a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst once described by the New York Times as ‘John Wayne in a blue suit’. He taught at Columbia and had co-authored a book about the usefulness of the interview in clinical situations. Didion was 66. She wasn’t seeing MacKinnon under duress: her daughter, Quintana, who was an alcoholic, had told her own psychiatrist that her mother was depressed and should see someone, which was like telling him she knew of a car that needed fuel or a dog that wanted a bone. Didion’s relationship with the blues was one of the things that defined her.

On first reading Didion’s bare, undigested notes from those sessions, I felt that the therapeutic drama was like a production of Ibsen’s The Wild Duck as directed by John Cassavetes. Between MacKinnon and Didion, the process of interviewing must have been pretty electrifying. ‘My only advantage as a reporter,’ she wrote in the preface to Slouching towards Bethlehem, ‘is that I am so physically small, so temperamentally unobtrusive and so neurotically inarticulate that people tend to forget that my presence runs counter to their best interests.’ Then there was the John Wayne thing: he was a hero of Didion’s childhood (‘In John Wayne’s world,’ she wrote in an early essay, ‘John Wayne was supposed to give the orders’). But it was the polar bears in the waiting room that really stuck in my mind. I tracked down that issue of National Geographic and tried to imagine someone reading about polar bear cubs in an office on a freezing New York day, knowing the reason she was there was to talk about the extreme vulnerability of her only child. ‘In spring,’ the story begins, ‘polar bear mothers in Manitoba’s Wapusk National Park emerge from dens with cubs three months old and ready to face the world. The sow has fasted for as long as eight months, but that doesn’t stop her young from demanding full access to her remaining reserves.’

Let’s back up for a moment here and appreciate what we have just read.

O’Hagan spotted the detail about the National Geographic. He wondered why Didion had specifically mentioned it. To borrow from the poet Edwin Morgan, nothing is not giving messages. O’Hagan then checked the date of Didion’s appointment and took the effort to seek out that very issue of the magazine. In doing so he unearthed a nugget of pure gold. The quote from the magazine about the mama bear and her life-draining cubs could not be more on point, given Didion’s growing realisation that her paralysing fear for her daughter was draining her dry.

The telling detail. I love this example of the journalist’s craft. A reporter with a novelist’s eye? Or a novelist with a reporter’s eye? Perhaps both.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Jaggy Thistle to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.